Our Research

Our research goal is to understand and predict the dynamics of land waters from local to global scales, including its interaction with Earth system and human society. To achieve this goal, we work on various science challenges on global hydrology/hydrodynamics mainly using modelling, remote sensing, and data integration approaches.

- Research Topic Overview.

- Global hydrodynamic modelling.

- Satellite Monitoring of Global Hydrodynamics.

- Global hydro-topography datasets.

- Global flood risk assessment.

If you are interested in detail: please also visit the list of publications.

Global Hydrodynamic Modelling

What is the dominant physical process that regulates the global water circulation? How significant is the impact of human activity and climate change on it? Through the modeling of global water circulation, we aim to fully understand the underlying mechanism. In our group, we work on modeling horizontal water flow in land areas. Our main research topics are related to the simulation of flood inundation, natural and anthoropogenic related water dynamics.

Global River Hydrodynamic Modeling [CaMa-Flood]

River is an important component of the global hydrological cycle, and it interacts with Earth’s climate and biogeochemical systems by transferring water and other materials from land to oceans. It also affects human society by providing water resources, while too much or too small river discharge causes disasters (i.e. flood, drought). Understanding and predicting river water dynamics is essential for representing rivers within global climate models and also for water resource planning and water-related disaster mitigation. However, modeling of river hydrodynamics on the global scale is difficult because of its multi-scale nature. While we have to consider the basin-wide water budget of continental rivers (spatial scale: larger than 1000km), the water movement is regulated by detailed topography of river channels and floodplains (spatial stale: smaller than 100m). To overcome this difficulty, we are working on developing a global river model CaMa-Flood (Catchment-based Macro-scale Floodplain), which can simulate river hydrodynamics very efficiently by representing flood inundation as sub-grid scale physics.

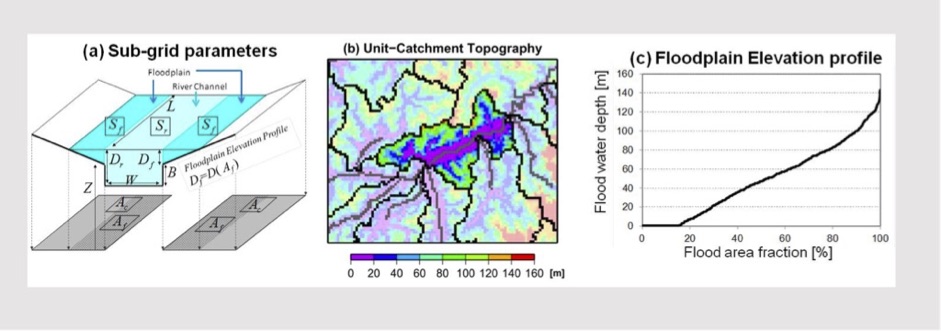

In order to represent the process of floodplain inundation, the river channel and floodplain topography are represented by sub-grid-scale topographic parameters. Sub-grid parameters such as ground elevation, unit-catchment area, channel length, and floodplain elevation profile are explicitly derived from fine-resolution satellite hydro-topography dataset. The floodplain elevation profile is a function that describes the relationship between the water level and inundated area for each grid cell, which is created by calculating the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the height of each fine-resolution pixel above the nearest downstream river channel pixel within each unit-catchment. The channel cross section parameters (i.e. channel width and depth) are derived empirically as a function of river discharge due to the lack of global-scale observations of channel cross sections. Using these sub-grid topography parameters, computationally-efficient but accurate simulation of river hydrodynamics is achieved.

Sub-grid topography representation in CaMa-Flood model.

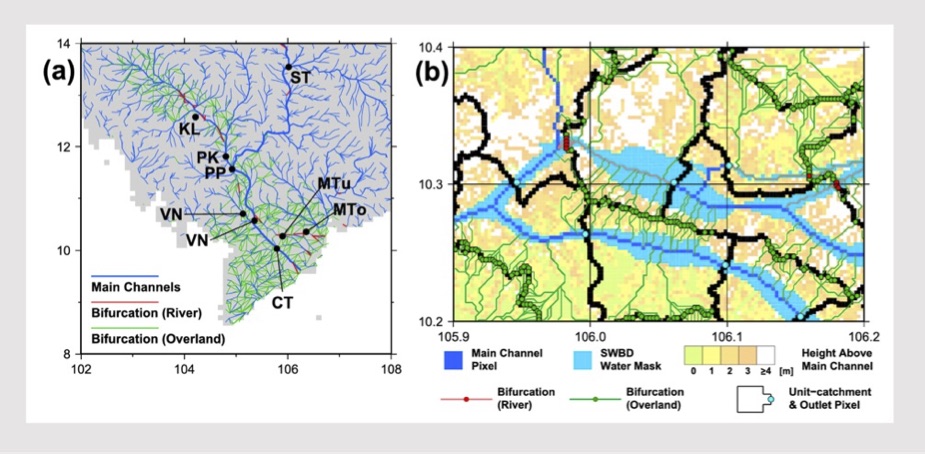

River bifurcation scheme

Bifurcation of river channels can be also represented by analyzing high-resolution topography. River mega deltas are one of the most vulnerable regions to flood, so it is important to apply global flood models in such areas. However, their divergent channel system is difficult to be simulated by global river models assuming that each grid cell in a river network map has only one downstream direction. We have developed a fully automated algorithm to create a reasonable representation of bifurcation channels in a global river network map. It searches flow pathways connecting two unit catchments represented as subgrid topographic parameters, and extracts bifurcation channels from the DEM and flow direction map.

Bifurcation channel representation in CaMa-Flood.

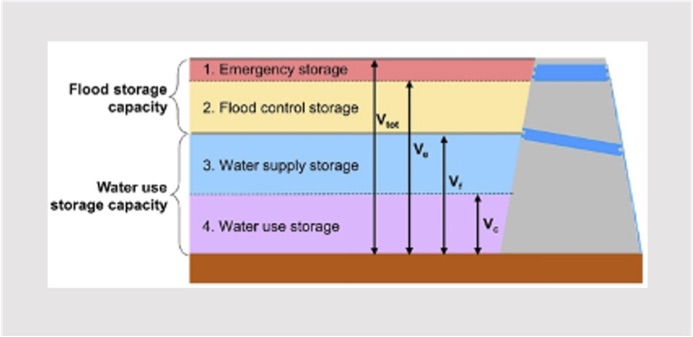

Reservoir operation scheme

Reservoir flood control operations are also implemented. This algorithm has fixed an error specific in river models using the diffusion equation can calculate backwater effects, that reservoir storage changes are buffered by upstream river storage. It defined three target water levels and corresponding volume from the bottom of a reservoir, and the operational rules were formulated for each zone to determine the reservoir outflow. Due to a lack of information on dams and reservoirs around the world, it estimates the required parameters of each reservoir by a novel method using data sets recently developed based on satellite observation. Furthermore, the algorithm for the operational rule was modified by introducing a new release coefficient such that the peak attenuation depended on the reservoir’s ability to regulate floods.

Reservoir representation in CaMa-Flood.

Representing Holizontal Water Dynamics in Land Models

Hillslope Hydrology in Global Land Model

Early on, land surface model (LSM) acted as key component of climate model to describe the surface boundary conditions, using quantitative methods to simulate the exchange of water and energy fluxes at the Earth surface–atmosphere interface. Previous LSM developers mainly investigated the land surface processes occurring in vertical dimensions, often oversimplifying the complex but significant horizontal phenomenon.

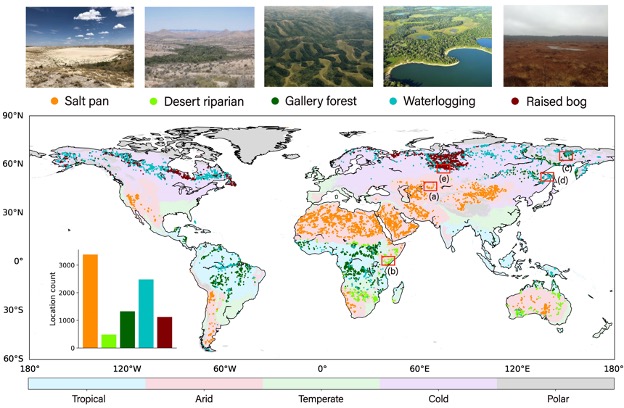

Nevertheless, the local topographic and hydrologic condition can profoundly differentiate the land surface process. For example, carbon emission over land waters (CO2 from stream and lake surface, methane from wetlands) is not negligible in global carbon budget studies, and horizontal water redistribution could control vegetation dynamics and water budgets. To manifest this, our study successfully detected many unique landscapes in the world which are controlled by the hillslope water dynamics, such as gallery forest and waterlogging. Their existence proves a widespread dominance of horizontal water on vegetation patterns, but it remains rarely considered in the current LSMs.

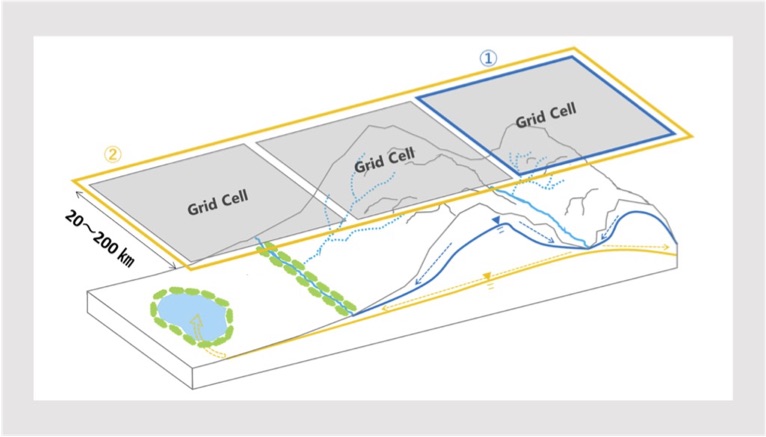

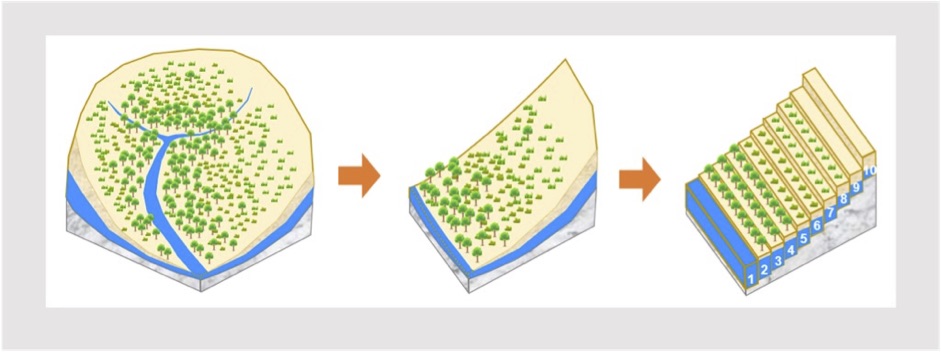

Later, LSM evolved into an individual tool to address the biogeochemical, hydrological, and energy cycles at the earth’s surface. In particular, the horizontal heterogeneity in land surface process became well considered. To represent the heterogeneity in hydrological process, we propose a multi-scale modeling approach in LSM to simulate the physical water movement from upper hill to downstream. Specifically, a catchment is theoretically collapsed into a neat representative hillslope, which is discretized into a pre-defined number of vertical height bands. By comparing the water table depths between neighboring bands, water exchange is calculated using Darcy’s law to simulate the water dynamics along hillslope. With the representation of detailed hydrological processes within the Earth system modelling framework, we expect to examine their impact on the global climate system.

Human activity in Global Water Resources Model

Human impacts on water circulation are recently becoming more and more important. Water withdrawal by humans for irrigation, industrial and domestic use is about 4000 km3, which accounts for about 9% of world river discharge. Also, reservoir operation greatly changes water flow. Reservoirs store water in times of surplus and release it in times of scarcity, thus they can mitigate or prevent the flood and ease water scarcity. There are about 60000 dams in the world according to ICOLD synthesis, and served for various purposes such as flood control, irrigation, water supply and hydropower.

Some global water resources models contain not only land surface models but also human water abstraction and reservoir operation. For example, one of global water resources models H08 consists of six sub-models, namely land surface, river routing, reservoir operation, crop growth, environmental flow (the flow required to maintain the natural environment of rivers) and water abstraction. After solving water and energy balance by land surface sub-model, accumulate runoff and calculate river discharge by river routing sub-model. Crop sub-model estimates crop calendar, then irrigation water demand and evapotranspiration from agricultural land are simulated.

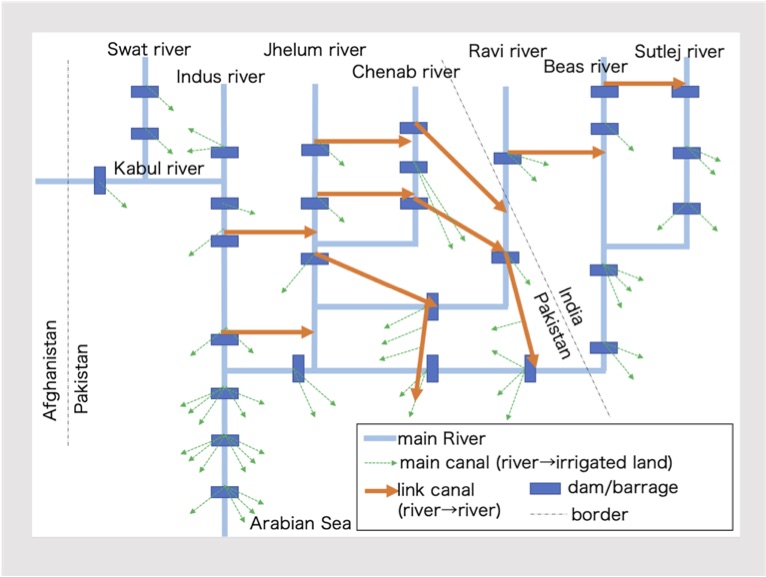

Recently global water resources models are applied at a spatial resolution of 2~10 km. Challenges of applying global models in a finer spatial scale are summarized as how to validate the result, expressing site-specific hydrological processes and water use practices, parameter regionalization, inter-grid-cell connection by water supply and drainage systems. Localization by tuning some hydrological parameters, adding local reservoir operation rules and local aqueducts, makes it capable of estimating natural and human water balance components at daily time scales and providing reliable information for regional water resource assessment.

Incorporating water supply and drainage systems into global water resources models has several challenges, such as data availability, complicated operation rules and representing diverse local water system structure in a uniformed scheme. Especially inter-basin water transfer annually deals with about 1700 km3 of water, which has a significant effect on water resources distribution. Implementing inter-basin water transfers into global hydrological models is still on the way, requires a new scheme overcoming the assumption that each grid cell in a river network map has only one downstream direction.

Example: water transfer in Indus basin